Our Western Chaps are best suited to your needs, whether you’re bull riding, staying warm, or just dressing to impress! Stop by or check out our selection.

Queen’s new crown

Chili is Dairy Queen’s dressing — make that crown — for its latest iteration of the GrillBurger. The Chili Meltdown tops a -half-pound cheeseburger with spicy, meaty sauce, showcasing the product’s versatility and enduring appeal.

Chili is Dairy Queen’s dressing — make that crown — for its latest iteration of the GrillBurger. The Chili Meltdown tops a -half-pound cheeseburger with spicy, meaty sauce, showcasing the product’s versatility and enduring appeal.

Dairy Queen VP Lane Schmiesing, who handles brand marketing for the fast fooder, says the product makes “a pretty strong appeal to a pretty important demographic for us, which is 18- to 34-year-old men.”

The Meltdown also is cost-effective, he says. “Sauce is inherent in chili, so we don’t necessarily have to condiment it with other types of sauces.”

Launched in September with the help of TV spots and newspaper inserts, as well as in-store promotions, DQ’s chili burger immediately shot up the popularity charts, where it occupied a spot next to other chain fixtures, including DQ’s cheeseburger and bacon cheeseburger. Sales have since settled down, but Schmiesing says the Meltdown remains a popular item.

“Our whole strategic focus for menu development is to create unique, crave-able flavors featuring products people associate with fast food but may not be able to get at every fast-food restaurant,”

Schmiesing says. Turns out DQ didn’t have to look too far for inspiration. The chain has used chili to top off hot dogs for nearly 50 years, so ladling a little of it over burgers was “a natural,” Schmiesing says.

DQ also serves chili soup-style, but the burger topping is more viscous, lest it compromise the integrity of the bun.

“It’s an indulgence item,” Schmiesing says. “It’s meat on top of meat. What more could a guy want?”

“Good farming is the greatest form of artistic expression. Farmers create the bridge between nature and human nourishment. Food as the product of the agricultural arts goes beyond any image on the wall of a gallery or museum. Good eating, in that sense, could be considered one of the most integrated forms of art appreciation.”

Is Grass-Fed Greener?

Grass-fed beef has garnered plenty of attention thanks to its health profile and taste, but will challenges of growing, processing and selling it put it out to pasture?

by Anne Spiselman

Whenever USDA issues a standard, it’s a safe bet that a product category has arrived. Whether it heralds a revolution is another story.

Despite its hype, the grass-fed beef category may be more evolutionary than revolutionary. Then again, it may be neither. It isn’t its health credentials that are in question. Omega-3S? Check. Fewer saturated fats? Check. More vitamins A, E and lineolic acid? Check, check and check.

Despite its hype, the grass-fed beef category may be more evolutionary than revolutionary. Then again, it may be neither. It isn’t its health credentials that are in question. Omega-3S? Check. Fewer saturated fats? Check. More vitamins A, E and lineolic acid? Check, check and check.

Nor is its flavor an acquired taste. Variously described as “more robust,” “less sweet” and “more natural” than conventional product, grass-fed generally holds its own in the taste sweepstakes.

No, at issue is whether small-scale operators can afford the additional time and expense required to fatten up grass-fed cattle, and whether consumers will pay a premium for a product they’ve never tasted, despite the apparent health benefits it confers.

So the jury is out. Some industry members contend grass-fed will likely remain a niche product. Others predict it will grow to account for as much as 10 percent of the U.S. beef market.

Now that would be revolutionary.

Now that would be revolutionary.

“Providing year-round grass with sufficient nutritional value to fatten cattle for consistent taste and tenderness is a challenge,” says Bill Kurtis, founder and CEO of Sedan, Kansas based Tallgrass Beef Co. “For ranchers, raising cattle entirely on grass increases the costs and the benefits. It’s an act of alchemy that transforms a maligned meat into a health food.”

SEEDS OF GROWTH

Grass-fed beef currently represents only a fraction of the nation’s beef supply less than a fraction, as a matter of fact. But that meager percentage translated into retail sales of $120 million last year, according to Tallgrass Beef COO Alien Williams, who also is a partner with the Jacob Alliance, a Canyon, Texas-based livestock consultancy.

Only about half of sales were domestic, the remainder deriving from places such as Australia, New Zealand and Uruguay, but Williams maintains that more than 1,200 U.S. ranchers have begun grass-finishing at least some of their beef. With so many seeds sown, grass-fed could grow up to 30 percent annually over the next five to 10 years, Williams says.

Less promising is the fact that he doesn’t see major processors getting into the act, as they have with natural and organic meats. “It’s not worth their time,” he says. “It would require a major financial commitment, and there would have to be a significant paradigm shift to build supply, which could take years.” Don’t expect Wal-Mart and other mainstream mega-chains to carry grass-fed any time soon either, he says.

Meanwhile, some of the usual suspects have begun stocking domestic grass-fed, in some cases to supplement or replace imported product. Meat from Vina, Calif. -based Panorama Natural Grass-Fed Beef debuted late last year in 22 Whole Foods Markets in Northern California, Portland, Ore., and Seattle. Panorama also supplies the 188 stores in Trader Joe’s Western division as well as smaller regional players on the order of Oakland, Calif.-based Farmer Joe’s.

Marc Blitstein, meat director for Boulder, Colo.based retailer Wild Oats, reports that organic grass-fed beef, which the retailer only recently introduced, already accounts for 10 percent of beef sales, despite its comparatively hefty price tag some $6.99 per pound for ground chuck and $19.99 for New York strip, as compared to $4.49 and $14.99 the retailer charges for comparable cuts from Coleman Natural Foods.

The other half of the equation is cost, no small consideration given that grass-fed cattle especially those grazing on open pasture gain weight more slowly than their grain-fed counterparts. Rather than being harvested at 14 to 18 months at 1,250 pounds, grass-fed cattle generally don’t reach their slaughter weight of 1,150 pounds until they are 24 to 30 months old. The grass sets the timeline and accounts for taste and texture, though it is subject to the vagaries of weather and other variables.

‘PART ART, PART SCIENCE’

Grass-fed companies positioning themselves for growth tend to contract with ranchers rather than raise their own herds. But first they must convince them to follow company protocols, then provide them with sufficient financial incentive to ensure cattle wind up in the pasture rather than the feedlot. They also must locate finishers that understand proper pasture rotation and other aspects of what Williams says is “part art, part science.”

Then there is the issue of locating and qualifying plants in close proximity to the finisher. Because few, if any, plants are dedicated to grass-fed product, operators must be persuaded to slaughter, cut and pack a relatively small number of cattle on a dedicated shift to ensure that product doesn’t mix with that from conventional cattle. None of it necessarily comes cheap.

Companies are meeting these challenges in a variety of ways. Dillon, Montana based La Cense Beef uses a seasonal model, with about 200 animals harvested annually in the fall. Animals are selected from a herd of 2,000 Black Angus cows and 1,000 yearlings that feast on lush pastures for at least 60 days once they reach the age of 14 months. All meat is processed at once, dry-aged for 19 days, then frozen, says COO Scan Hays, who says he would like the last of his product to roll out the door as next year’s rolls in.

The year-old Tallgrass contracts with several ranches and five finishers to accommodate a business that is doubling monthly. Each animal undergoes ultrasound testing to evaluate its marbling, tenderness, back fat and carcass cutout. Current yield 1859 percent, though the goal is the 60 percent to 62. percent range, like commodity beef. Though Tallgrass harvested only 20 head in July, some 2,000 to 3,000 more are being finished. Product is USDA graded for carcass quality but isn’t marketed by grade. The resulting beef is 60 percent Choice, compared with a national average of 42 percent to 45 percent for grain-fed.

Genetics and feed play a big role in those results, as they do with Panorama’s. Panorama cattle are all Black and Red Angus that spend their last 30 to 60 days in a “conditioning corral” on rations of grass-hay and alfalfa supplemented with rice bran and almond hulls for energy and roughage. CEO Mac Graves says the breeds were chosen because they readily deposit intramuscular fat on a grass-based diet. The finishing regimen, he says, allows cattle to reach their harvest weight in just 14 to 18 months while ensuring a tender, tasty product.

Genetics and feed play a big role in those results, as they do with Panorama’s. Panorama cattle are all Black and Red Angus that spend their last 30 to 60 days in a “conditioning corral” on rations of grass-hay and alfalfa supplemented with rice bran and almond hulls for energy and roughage. CEO Mac Graves says the breeds were chosen because they readily deposit intramuscular fat on a grass-based diet. The finishing regimen, he says, allows cattle to reach their harvest weight in just 14 to 18 months while ensuring a tender, tasty product.

The 4-year-old company adheres to a “Born and Raised in the USA” verification program, contracts with up to 45 West Coast ranches and harvests 145 head of naturally raised cattle per week, making it the largest grass-fed provider in the nation. Recently, Panorama also began raising and harvesting organic product due to the category’s strong growth potential. “Consumers have come to recognize that ‘natural’ can be almost anything, and appreciate the stricter protocols of organic,” Graves observes.

Although he won’t disclose sales figures, Graves says about two-thirds of his business involves retail distribution, with steak sales having grown about 25 percent in the past few months alone. He also is active in the value-added segment, having recently developed four types of sausage and, for Trader Joe’s, Cowday Quick-Eye Steak, a thin-sliced, ready-to-cook eye of round that includes a packet of brandy mushroom sauce.

As with any emerging category, marketing is key to moving product off shelves, or off electronic shelves. This past spring, La Cense launched a Web site to promote and sell grass-fed, and

Hays says he’s pleased with the traffic he’s getting. Though he has a ways to go, he says he hopes one day to be the “Omaha Steaks of grass-fed” a goal shared more or less realistically by all who embrace the category.

“Good farming is the greatest form of artistic expression. Farmers create the bridge between nature and human nourishment. Food as the product of the agricultural arts goes beyond any image on the wall of a gallery or museum. Good eating, in that sense, could be considered one of the most integrated forms of art appreciation.”

The Burger is Still King

The almighty burger keeps reinventing itself to remain relevant, and these days ketchup, cheese and onions are the least of it.

The almighty burger keeps reinventing itself to remain relevant, and these days ketchup, cheese and onions are the least of it.

By Ariel Tompkins, contributing editor

Consumers these days hear a lot about regional American cuisine: Southwestern, low country, and low, low country, to name a few. But, be it in Texas, the Carolinas or points between, the simple hamburger remains the quintessential American food.

It is the preferred menu item among American men, and second only to French fries among American women. The average American eats one every other day. Five of the nation’s largest restaurant chains menu it, and it accounts for four of every 10 sandwiches consumed in U.S. restaurants. As one pundit once put it, it is to restaurants what wings are to aviation. Fads may come and go, but the hamburger continues to defy gravity.

Nevertheless, processors and food service operators still fret that hamburger consumption is declining due to new so-called healthier options, including salads, yogurts and chicken sandwiches.

It needn’t be the case, says NPD Group Vice President Harry Balzer. Burger operators tend to keep introducing double and triple burgers intended for young men. Why, Balzer wonders, has no one created a burger especially for women?

Instead, McDonald’s and other burger-centric chains typically add chicken and the like to attract women, though it’s worth noting that the Oak Brook, 111.-based quick-service restaurant abides by the 80-20 rule — meaning 80 percent of its profits derive from 20 percent of its products, led by its flagship burgers and fries. McDonald’s does put new spins on old favorites sometimes, though. Later this year, it plans to introduce a hip-hop campaign to promote the eternal cool of its 35-year-old Big Mac.

Instead, McDonald’s and other burger-centric chains typically add chicken and the like to attract women, though it’s worth noting that the Oak Brook, 111.-based quick-service restaurant abides by the 80-20 rule — meaning 80 percent of its profits derive from 20 percent of its products, led by its flagship burgers and fries. McDonald’s does put new spins on old favorites sometimes, though. Later this year, it plans to introduce a hip-hop campaign to promote the eternal cool of its 35-year-old Big Mac.

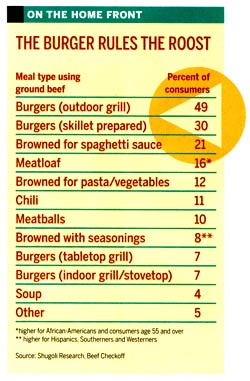

On the home front, hamburger accounts for 8.9 percent of all eating occasions, and ground beef for 59 per-cent of all fresh beef served at the dining room table. Sales of frozen ground beef totaled almost $305 million for the 52 weeks ended Jan. 1, 2005, according to research firm ACNielsen.

“Hamburger is the most favored product in the retail beef line,” says Randy Irion, director of retail marketing for the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association. “Most beef items are purchased for a particular occasion, but consumers buy hamburger like milk or bread, because there are so many ways to use it.”

Versatile it is. In Mississippi and Tennessee, there is the soy-enhanced “slug burger” and flour-and-water-cut dough burger, while Texans like their burgers topped with beans, Fritos and Cheez Whiz.

Now, there’s regional cuisine for you.

Lean, leaner, leanest – and chub packs

If you want to see what’s sizzling on the grill, you might as well start at the top: Wichita, Kan.-based Cargill Meat Solutions, the nation’s largest producer of ground beef. Charlie Fox, Cargill’s vice president and business manager of ground beef, says hamburger consumption patterns are changing, as are the category’s products.

If you want to see what’s sizzling on the grill, you might as well start at the top: Wichita, Kan.-based Cargill Meat Solutions, the nation’s largest producer of ground beef. Charlie Fox, Cargill’s vice president and business manager of ground beef, says hamburger consumption patterns are changing, as are the category’s products.

Meatingplace: Have sales of hamburger patties been affected by the “healthy movement”?

FOX: Yes, our information shows that 70 percent to 77 percent lean volume has been flat over the past 52 weeks. But data also shows that 85 percent to 89 percent lean is up about 8 percent, and that 90 percent to 94 percent lean is up 6 percent over last year. We’re also finding that source grinds (chuck, round and sirloin) are showing increases in volume. Our 96 percent higher-lean, lower-fat product is a steady performer.

M: What new case-ready products are you developing?

F: Our REDI-Fresh technology is a convenient, leak-proof package with a prominent use-by/freeze-by date. It provides a longer fresh color. Some 100 million REDI-Fresh packages have been sold over the past year or so.

M: What is Cargill doing to brand and merchandise hamburger?

F: We have two business-to-business brands in the United States: Excel and Taylor. Some of our consumer brands include Sterling Silver, Angus Pride and Century Farm. We’re licensed to distribute Certified Angus beef. Chubs are becoming increasingly popular as well. We also have a T ‘n T brand, referring to thick and tender. You can cook it at 160 degrees F and hold it for hours. It does well in food service, and we’re evaluating how we can expand it.

M: What food safety challenges are you facing?

F: We have a leadership role in many pathogen intervention technologies. We also do intervention verification testing, or industry pathogen testing. We test by lot versus total shift, allowing us to minimize the potential of a recall.

Bigger Burgers – Fatter Returns

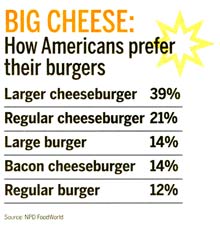

Big is in, particularly among the hamburger’s core consumer — teenagers and adult males under the age of 45. While burger sales in the food service sector rose a modest 2 percent last year, sales of bigger, pricier burgers grew more than twice that fast — 5 percent, according to Russ Klein, global marketing chief of fast-food chain Burger King.

Big is in, particularly among the hamburger’s core consumer — teenagers and adult males under the age of 45. While burger sales in the food service sector rose a modest 2 percent last year, sales of bigger, pricier burgers grew more than twice that fast — 5 percent, according to Russ Klein, global marketing chief of fast-food chain Burger King.

On the strength of its Angus Thick-burger, which weighs in at a whopping 2/3 pound, burger chain Hardee’s has seen burger sales in its 2,050 U.S. outlets climb 20 percent since 2003. Hardee’s outdid itself in 2004 by introducing the Monster Thickburger, two 1/3-lb. Angus patties, four strips of bacon and three slices of American cheese and pickles, all on a buttered sesame-seed bun slathered with mayonnaise. It’s twice the size of McDonald’s Big Mac, contains 1,420 calories and has been a sensation among men ages 18 to 34 years old.

Last year, Clearfield, Pa.-based fast-casual restaurant Denny’s Beer Barrel Pub added the Beer Barrel Belly Buster, a 15-lb. burger molded into a 20-in.-diameter patty on a specially baked bun, to its menu and called it the world’s largest burger. The restaurant challenges any two patrons to eat it within a three-hour sitting. If they do, they get it for free. Others must pay a $30 tab.

Burger Buzz: New Flavors and Formats

THE BREAKFAST BURGER: With about 10 percent of all fast-food sales generated in the morning, Carpinteria, Calif.-based burger maker Carl’s Jr. asked itself, why not burgers for breakfast, especially for workers just off the night shift? The chain responded with a char broiled breakfast burger topped with a fried egg, which now accounts for 40 percent of breakfast sales at Carl’s 1,000 restaurants.

THE TAPA’S BURGER: Fast-casual chain Ruby Tuesday’s now menus four mini beefburgers as an entree. The burgers can be eaten as a meal or shared as an appetizer before patrons dive into the chain’s Colossal Burger — two 1/2-lb. burgers on a triple-decker bun.

THE JALAPENO BURGER: Introduced in January, Carl’s Jr.’s Jalapeno Burger “would have been rejected not that long ago because of its limited appeal,” says company marketing VP Brad Haley. “But things have changed dramatically in a fairly short time. Salsa is America’s favorite condiment, and Carl’s Jr. recently has found success with a variety of spicy [items]. So the timing seemed right.”

THE JALAPENO BURGER: Introduced in January, Carl’s Jr.’s Jalapeno Burger “would have been rejected not that long ago because of its limited appeal,” says company marketing VP Brad Haley. “But things have changed dramatically in a fairly short time. Salsa is America’s favorite condiment, and Carl’s Jr. recently has found success with a variety of spicy [items]. So the timing seemed right.”

The new Jalapeno Burger is not only topped with sliced jalapenos, but pepper jack cheese, Santa Fe sauce, sliced onion, tomato and lettuce.

THE WELLNESS BURGER: Ground beef normally isn’t considered a vehicle for wellness foods ingredients, but processor Cardinal Foods blends the fatty acid omega-3 into its ground beef via a thermo-resistant, thermo-irreversible gel. Retailers IGA, Sobeys and Safeway carry the product in their Canadian stores. The ground beef contains 300 mg of omega-3, sufficient for a food claim.

THE ‘IN’ BURGER: Burger consumers told Whole Foods Market they were bored with plain old burgers, so the retailer stopped piling on the toppings and started mixing them into the ground beef. The burgers contain diced and precooked ingredients such as cheese, bacon, mushrooms and onions.

“Good farming is the greatest form of artistic expression. Farmers create the bridge between nature and human nourishment. Food as the product of the agricultural arts goes beyond any image on the wall of a gallery or museum. Good eating, in that sense, could be considered one of the most integrated forms of art appreciation.”